Urbana, Ohio

Urbana, Ohio | |

|---|---|

Downtown Urbana | |

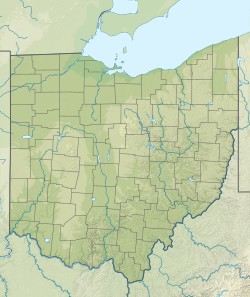

Location of Urbana in Champaign County | |

| Coordinates: 40°07′12″N 83°44′50″W / 40.12000°N 83.74722°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Champaign |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bill Bean |

| Area | |

• Total | 7.91 sq mi (20.49 km2) |

| • Land | 7.91 sq mi (20.49 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,043 ft (318 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 11,115 |

| • Density | 1,405.18/sq mi (542.54/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 43078 |

| Area code(s) | 937, 326 |

| FIPS code | 39-79072[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2397096[2] |

| Website | http://urbanaohio.com/ |

Urbana is a city in and the county seat of Champaign County, Ohio, United States,[4] about 34 miles (55 km) northeast of Dayton and 41 miles (66 km) west of Columbus. The population was 11,115 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Urbana micropolitan area. Urbana was laid out in 1805, and for a time in 1812 was the headquarters of the Northwestern army during the War of 1812. It is the burial place of the explorer and soldier Simon Kenton. The city was home to Urbana University and Curry Normal and Industrial Institute, a school for African American students.

History

[edit]Champaign County was formed on February 20, 1805 following the American Revolution and the Northwest Indian War. Colonel William Ward, a Virginian who had settled in the Mad River Valley with Simon Kenton in 1799, purchased 160 acres which he considered the logical and most acceptable site for Champaign's county seat. He approached the county commissioners with a proposition to locate the seat of the new county on this tract. Ward suggested that site to divided into 212 lots and 22 out-lots, half of which, selected alternately, were to be given to the county and while Ward would retain the remainder. Ward also offered two lots for a cemetery and a tract for the public square. The county commissioners approved the proposal, and Ward, with Joseph C. Vance, entered into a written agreement on October 11, 1805. Ward and Vance named the new county seat, Urbana.[5]

The origin of the name 'Urbana' is unclear; however, it is thought that Ward and Vance used the Latin word 'urbs', which means city.[6] Antrim provides the following theory: "It is said by some that Mr. Ward named the town from the word Urbanity, but I think it is quite likely he named it from an old Roman custom of dividing their people into different classes – one class, the Plebeians, and this again divided into two classes – Plebs Rustica and Plebs Urbana. The Plebs Rustica lived in the rural districts and were farmers, while the Plebs Urbana lived in villages and were mechanics and artisans."[7] Others feel that Ward and Vance chose to name it from a town in Virginia, possibly Urbanna, but this seems unlikely. Urbanna means 'City of Anne' and was named for the English queen. It is more likely that two Revolutionary War veterans would turn to Latin rather than honor their former foe. A review in 1939 shows that of the 12 cities in the United States named "Urbana", the city in Ohio was the first.[8]

When Ward delegated Vance to survey the site, there were no platted towns between Detroit and Springfield to use as a model. Nevertheless, Vance and Ward planned Urbana systematically. They provided for an ample public square, and laid the streets in an orderly pattern with no deviations for bogs and swamps.[6]

By 1833, Urbana contained a courthouse and jail, one printing office, a church, a market house, nine mercantile stores, and 120 houses.[9]

On June 4, 1897, residents of Urbana formed a lynch mob and fought their way into the town jail to remove Charles Mitchell, a black man who was suspect in the killing of a white. Crowds of men had been forming for more than a day. The mob hanged Mitchell in the courtyard of the courthouse in the middle of the night. Trying to protect him, Sheriff McCain had summoned the state militia, led by Captain Leonard. After the mob fired into the jail, the militia returned at least five shots, killing Harry Bell, one of the white mob, and wounding others. When the lynch mob gained entry after 2:30 am, the sheriff withdrew militia forces to an upper floor in retreat.[10]

On June 21, 2009, a skatepark was added to Urbana's Melvin Miller Park. In November 2013, Damian Prendergast, who was a local skateboarder, died from germ cell cancer. Following his death, his high school class raised $700 and support to dedicate the skatepark in Damian's name.[11][12]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.77 square miles (20.12 km2), of which 7.75 square miles (20.07 km2) is land and 0.02 square miles (0.05 km2) is water.[13]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 644 | — | |

| 1830 | 1,102 | 71.1% | |

| 1840 | 1,070 | −2.9% | |

| 1850 | 2,020 | 88.8% | |

| 1860 | 3,429 | 69.8% | |

| 1870 | 4,276 | 24.7% | |

| 1880 | 6,252 | 46.2% | |

| 1890 | 6,510 | 4.1% | |

| 1900 | 6,808 | 4.6% | |

| 1910 | 7,739 | 13.7% | |

| 1920 | 7,621 | −1.5% | |

| 1930 | 7,742 | 1.6% | |

| 1940 | 8,335 | 7.7% | |

| 1950 | 9,335 | 12.0% | |

| 1960 | 10,461 | 12.1% | |

| 1970 | 11,237 | 7.4% | |

| 1980 | 10,774 | −4.1% | |

| 1990 | 11,353 | 5.4% | |

| 2000 | 11,613 | 2.3% | |

| 2010 | 11,793 | 1.5% | |

| 2020 | 11,115 | −5.7% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 11,125 | 0.1% | |

| [3][14][15][16][17] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[18] of 2010, there were 11,793 people, 4,808 households, and 2,932 families living in the city. The population density was 1,521.7 inhabitants per square mile (587.5/km2). There were 5,401 housing units at an average density of 696.9 per square mile (269.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.7% White, 5.4% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.7% from other races, and 3.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.0% of the population.

There were 4,808 households, of which 31.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.3% were married couples living together, 14.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.0% were non-families. 33.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.34 and the average family size was 2.95.

The median age in the city was 38.2 years. 23.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.4% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.1% were from 25 to 44; 25.3% were from 45 to 64; and 16.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.1% male and 52.9% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 11,613 people, 4,859 households, and 2,998 families living in the city. The population density was 1,702.3 inhabitants per square mile (657.3/km2). There were 5,210 housing units at an average density of 763.7 per square mile (294.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.03% White, 5.95% African American, 0.34% Native American, 0.30% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.48% from other races, and 1.88% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.08% of the population.

There were 4,859 households, out of which 29.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.2% were married couples living together, 11.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.3% were non-families. 33.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the city the population was spread out, with 23.7% under the age of 18, 9.8% from 18 to 24, 27.9% from 25 to 44, 22.4% from 45 to 64, and 16.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $33,702, and the median income for a family was $42,857. Males had a median income of $33,092 versus $26,817 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,831. About 7.2% of families and 10.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.3% of those under age 18 and 7.6% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]

Several companies have facilities in Urbana, including Rittal, Honeywell Aerospace, Honeywell Inc., Control Industries, Freshwater Farms, Bolder & Co Creative Studio. A variety of services are located in buildings around the Urbana Monument Square Historic District, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Businesses in the square include banks, accounting, fine dining, bars, and personal care. The Champaign County Farmers Market is held weekly in downtown Urbana. In a contest sponsored by the American Farmland Trust, the market was voted as one of America's four favorite farmers' markets.[19] Urbana is also home to the annual Simon Kenton Chili Cook-Off that takes place downtown in the monument square.[20]

Education

[edit]Urbana is primarily served by the Urbana City School District, which includes Urbana High School (9–12) and a pre-k through 8 building. Both the high school and pre-k–8 were finished in 2018, after receiving grants for new school buildings. The original castle building from the high school still stands, but is no longer used. The new high school is on Washington Ave. and the elementary and middle school is south of Urbana on US 68.

The city was home to Urbana University from 1850 until 2020. It offered liberal arts tertiary-education opportunities in a small college environment. Serving about 1500 students, it offered 28 undergraduate majors in a variety of disciplines; graduate degrees in Business Administration, Criminal Justice, Education and Nursing; and opportunities for international students desiring to study in the United States.

Urbana has a public library, a branch of the Champaign County Public Library.[21]

Transportation

[edit]Infrastructure

[edit]- Urbana was a stop along the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, which connected Pittsburgh to Chicago and St. Louis.

- Urbana's municipal airport, Grimes Field, is home to the Champaign Aviation Museum. A museum known for its restoration of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and other historic aircraft.[22]

Notable people

[edit]- Clancy Brown – born in Urbana in 1959, producer and actor, son of Congressman Bud Brown (below).

- Clarence J. "Bud" Brown Jr., US Representative (1965 to 1983), former publisher of the Urbana Daily Citizen

- Call Cobbs Jr. (1911-1971), jazz pianist and organist

- Moses Bledso Corwin – attorney and member of United States House of Representatives

- Andy Detwiler - farmer

- Elias Franklin Drake – politician and businessman, born in Urbana

- Pete Dye – golf course architect voted into the Hall of Fame; grew up in Urbana

- Robert Morton Duncan – lawyer and jurist

- Robert L. Eichelberger – United States Army general in the South West Pacific Area during World War II

- Warren G. Grimes (1898–1975) – "Father of the Aircraft Lighting Industry"

- Charles T. Hinde – businessman and riverboat captain

- Edmund C. Hinde – miner during the California Gold Rush

- Robert R. Hitt – United States Assistant Secretary of State, born in Urbana in 1834

- Raymond Hubbell – composer of musicals, including the song "Poor Butterfly"

- Jim Jordan – Representative for Ohio's 4th district

- Michael Kent – comedian and magician

- Simon Kenton – frontiersman; buried in Urbana

- Tony Locke – Arena Football League wide receiver

- Beth Macy – journalist and non-fiction writer; grew up in Urbana

- Joseph Vance – 13th Governor of Ohio; lived in Urbana

- Martin R. M. Wallace – Civil War general, born in Urbana

- W. H. L. Wallace – Civil War general, born in Urbana

- Colonel William Ward – founder of Urbana

- John Quincy Adams Ward – sculptor of the George Washington statue in New York City

- Edgar Melville Ward – painter and educator

- Brand Whitlock – born and raised in Urbana; four-time mayor of Toledo, Ohio

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Urbana, Ohio

- ^ a b c "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Evan P. Middleton (1917). History of Champaign County, Ohio Its People, Industries and Institutions. B.F. Bowen. pp. 1089.

- ^ a b Writers' Program (Ohio) (1942). Urbana and Champaign county. Urbana, O., Gaumer publishing company.

- ^ Antrim, Joshua (1872). The history of Champaign and Logan counties: from their first settlement. Bellefontaine, Ohio : Press Printing Co. pp. 5.

- ^ "Urbana claims honor of first using name". The Evening Review (East Liverpool, Ohio). February 10, 1939. p. 22.

- ^ Kilbourn, John (1833). The Ohio Gazetteer, or, a Topographical Dictionary. Scott and Wright. pp. 458. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ "A Lynching at Urbana". The New York Times. June 6, 1897.

- ^ "Melvin Miller Park". urbanaohio.com. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Urbana students dedicate skate park to classmate who died of cancer". springfieldnewssun.com. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Population: Ohio" (PDF). 1930 US Census. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ "Number of Inhabitants: Ohio" (PDF). 18th Census of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. 1960. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Ohio: Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Urbana city, Ohio". census.gov. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ Morrill, Jennifer. "Champaign County, Ohio Farmers Market Voted America’s Favorite Farmers Market" Archived December 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, American Farmland Trust, September 28, 2010.

- ^ "index". chilicookoffofurbana.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "Hours & Locations". Champaign County Public Library. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- ^ "Bringing a B-17 back to life". aopa.org. October 13, 2015. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2019.